This is Part 1 of a two-part series analyzing the impact of an amendment to the House Homeland appropriations bill on the H-2A and H-2B visa programs.

Key takeaways:

- The government funding bill for the Department of Homeland Security may include a rider amendment that would expand the H-2A visa program for seasonal farm jobs. This amendment (originally known as Amendment #1 but later dubbed the Bipartisan Visa En Bloc amendment) proposes to open the H-2A visa program to year-round occupations.

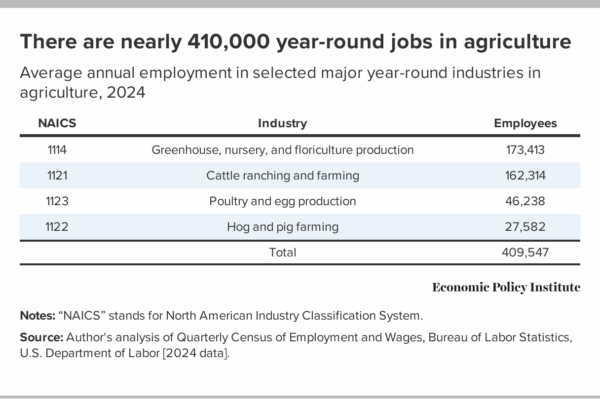

- There were 410,000 year-round jobs in agriculture and 353,000 seasonal H-2A workers in 2024.

- The Trump Department of Labor has issued a new 2026 H-2A Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR) to set H-2A wages. Based on their own estimates, the 2026 H-2A AEWR will result in a $24 billion pay cut for H-2A farmworkers over 10 years and incentivize growth in the H-2A program to 500,000 jobs a year. EPI has estimated that U.S. farmworkers will lose $2.7 to 3.3 billion in wages per year.

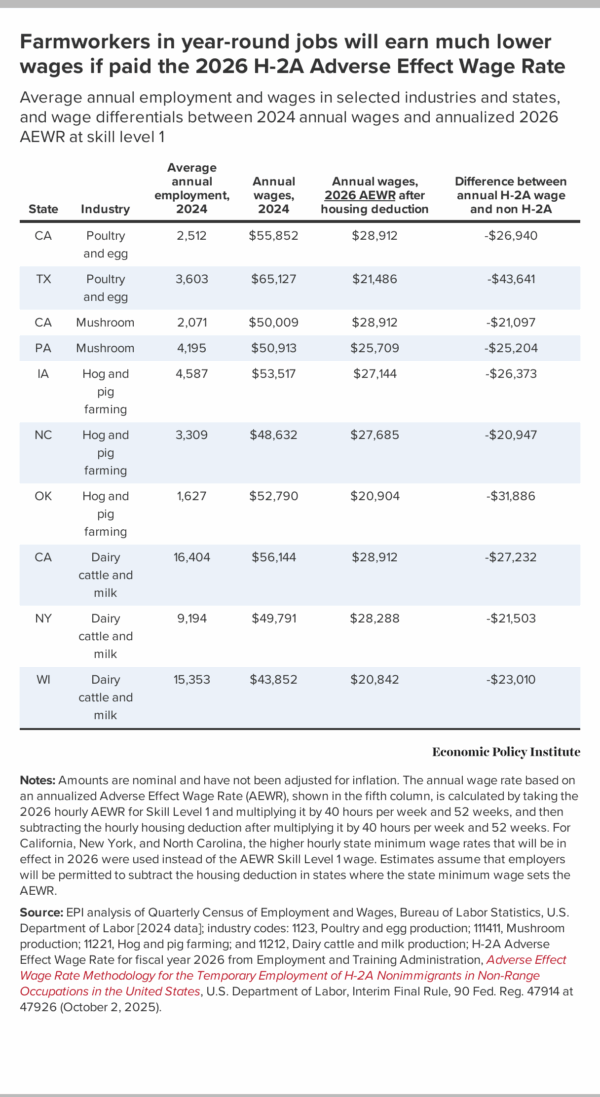

- If employers are allowed to use H-2A visas for year-round jobs via the House Homeland appropriations rider, farmworkers in those jobs will see massive pay cuts of $20,000 to $40,000 per year, starting in 2026.

- The Trump DOL wage reductions combined with H-2A visas for year-round jobs could expand the H-2A program to 900,000 workers in 2034, meaning that workers on temporary visas would account for 42% of average annual employment in agriculture.

- This rider in Congress and the proposed regulation at DOL would only benefit farm employers, allowing them to hire workers they can control for as little pay as possible. These changes would drastically lower pay for all farmworkers and lead to job losses for U.S. workers, a complete reversal from the Trump administration’s original claims that U.S. workers would fill the farm jobs left open due to deportations.

For well over a decade now—time and time and time and time again—Congress has been making policy changes to temporary work visa programs not through the normal process of debating and passing legislation, but through a backdoor process. This involves amendments to annual appropriations legislation (known as “riders”) that fund the U.S. government. Riders that make policy changes are much more likely to pass without much public notice, debate, or pushback relative to dedicated legislation, since they are smaller parts of larger, must-pass legislation to fund the whole U.S. government. The significant changes proposed or passed in riders over the past decade have all pushed temporary work visa programs in the same direction: expanding and deregulating the H-2A and H-2B visa programs, which benefits employers at the expense of U.S. workers and hundreds of thousands of migrant workers who will continue to see reduced wages and poorer working conditions. It’s already clear that low-wage work visa programs won’t be improved during the Trump administration; instead, they’ll be made much worse.

This fiscal year, there is a particular urgency around the riders to expand and deregulate the H-2A and H-2B visa programs, in light of the Trump administration’s mass deportation effort that is arresting and deporting workers at a breakneck pace, as well as canceling temporary immigration protections that provided work authorization to millions. The Trump administration got the ball rolling on this effort with a new proposed H-2A wage regulation issued by the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) on October 2, 2025. This proposed regulation contains a stunning admission: The administration’s mass deportation effort is likely to raise food prices. DOL’s solution to this problem of the administration’s own creation is an irrational and anti-worker solution. Instead of pushing the administration from within to stop their campaign of mass deportation, DOL proposes to lower farmworker wages by $24 billion over the next 10 years.

Having seen this proposed rule, employers who are heavily reliant on migrant laborers—especially those in the hospitality, construction, and agricultural industries—can now be confident they have a friendly administration willing to dismantle labor standards and are lobbying furiously for more work visas that allow them to employ a vulnerable workforce. Employers are making the case that H-2 visas are “a workforce issue, not immigration,” as well as an essential service that must continue to function even during the recent government shutdown. A number of lawmakers and the Trump administration seem to agree.

The latest legislative vehicle that has a chance at furthering these goals is a rider that the Homeland Security subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee proposed and passed. It was originally known as Amendment #1 but was later dubbed the “Bipartisan Visa En Bloc” amendment. As Politico Pro reported, “House appropriators from both parties came together…to back big changes to visa policies that would boost the number of seasonal workers who can come to the United States.” The rider was cosponsored by three Republicans and one Democrat (but the Democrat was Henry Cuellar (D-Texas), the recent recipient of a pardon from Trump for federal bribery charges). However, it’s worth noting that because rider passed by a voice vote, there is no on-the-record vote tally showing who voted for it.

The rider still has a long way to go before becoming law and will also depend on whether an omnibus government spending bill is ultimately passed for fiscal year 2026. As of the time of publication, the Senate has not yet released their version of a Homeland Security appropriations bill. To become law, the Senate would also have to adopt the same rider provision for it to become part of the broader omnibus appropriations legislation. Nevertheless, the rider is a statement of intent from legislators who are willing to go to bat for employers seeking new exploitable and underpaid migrant workers to replace their long-term immigrant workers who have been deported or lost status.

Below is a summary of the four major changes that the Bipartisan Visa En Bloc rider amendment would make to the H-2A and H-2B visa programs. Only the first major change is discussed in this explainer, but a follow-up to this blog post will discuss the other three changes. Under the rider:

- Employers would be permitted to hire H-2A farmworkers to fill year-round jobs.

- The H-2B visa program would be expanded by at least 100,000 workers relative to its size in 2024.

- H-2B workers employed at carnivals, traveling fairs, and circuses would be moved to the P visa program, a program that has no wage rules or worker protections and over which DOL has no formal oversight role.

- DHS would not be permitted to spend funds to implement the January 2024 regulation that incrementally improves rights and protections for H-2A and H-2B workers. This regulation allows them to be eligible for green cards through existing pathways and helps them more easily change employers, reducing the indentured nature of the visa programs, and requires additional scrutiny on employer applications if they’ve committed certain violations.

The H-2A program has expanded rapidly and is rife with abuse

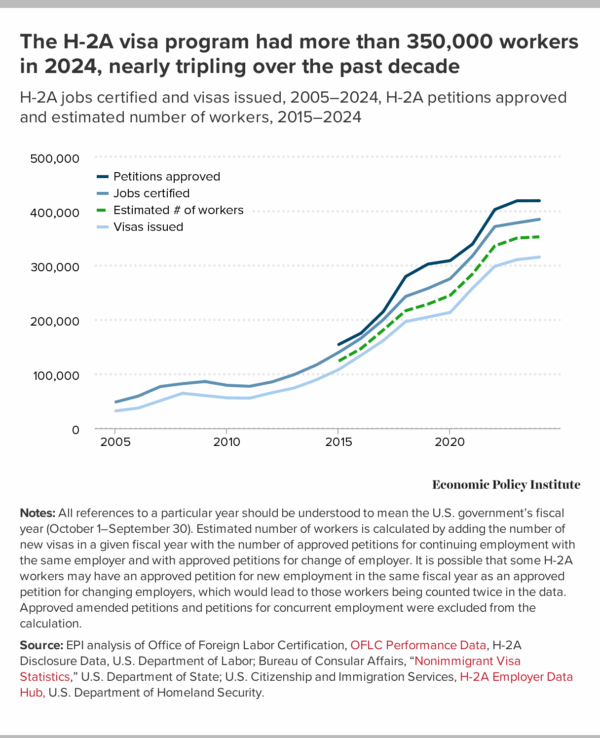

Employers use the H-2A visa program to fill seasonal and temporary jobs in agriculture, after employers go through a (mostly pro forma) process to prove that they could not find an available U.S. worker to hire. There is no annual limit on the number of H-2A workers that can be hired, and H-2A has in recent years been the fastest-growing U.S. work visa program, tripling over the past decade. Figure A shows the three available data sets on H-2A job certifications, petitions, and visas, as well as an estimate of the total number of H-2A workers between 2015 and 2024, with 352,682 H-2A workers estimated to have been employed in the United States last year. The vast majority of H-2A workers are employed on crop farms, picking fruits and vegetables, and the average duration of an H-2A job is roughly six months.

Figure A

There have been countless exposés from journalists and advocates that reveal how H-2A farmworkers are indentured to their employers, frequently robbed, exploited, victimized, and trafficked, and how the main source of wage and hour violations on farms comes from employers breaking H-2A rules.

The rider adopted in the House would allow H-2A workers to be employed in year-round jobs—which is currently prohibited—expanding the scope of the program and allowing H-2A workers to fill jobs on dairy, livestock, and poultry and egg farms, as well as in nurseries and greenhouses and other nonseasonal agricultural occupations. This would be a major change to H-2A, and it has long been a demand of agribusiness.

Making H-2A year-round raises three key questions:

- How many permanent, year-round jobs might be impacted?

- How will farmworker wages be impacted?

- How much will the H-2A program expand?

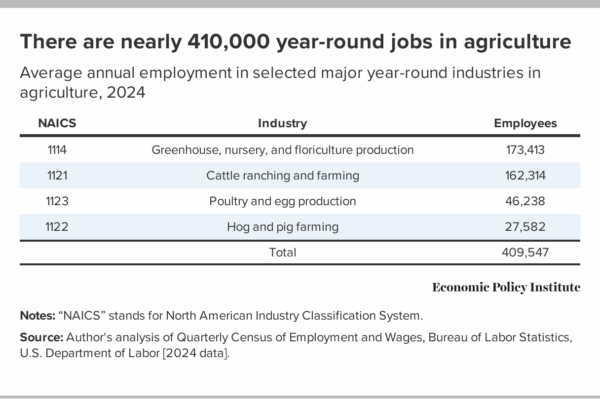

There are 410,000 year-round jobs in agriculture

For an answer to the first question, see Table 1, which lists four of the major agricultural industries employing farmworkers year-round, the largest of which are greenhouse and dairy jobs. Together they total nearly 410,000 full-time equivalent jobs. The industries listed do not include the many year-round (or nearly year-round) jobs that can be found on crop farms, including equipment operators and supervisors. In total, it’s possible that up to one-third of the total 1.6 million full-time equivalent jobs in agriculture could be year-round.

Table 1

DOL’s new Adverse Effect Wage Rate will result in a pay cut for H-2A workers and U.S. workers that will line the pockets of employers by billions

DOL’s new Adverse Effect Wage Rate will result in a pay cut for H-2A workers and U.S. workers that will line the pockets of employers by billions

Next, let’s consider what would happen to the wages of farmworkers in year-round occupations if the H-2A visa program were expanded to include them.

The wages of nearly all H-2A farmworkers are set by the Adverse Effect Wage Rate (AEWR), unless the federal, state, or local hourly minimum wages are higher, or if there is an applicable local prevailing wage or collective bargaining agreement in place. The purpose of the AEWR is to ensure that H-2A workers are paid a wage that is consistent with U.S. wage standards and prevent adverse impacts of H-2A employment on the wages of farmworkers in the United States.

On October 2, 2025, DOL issued an interim final rule laying out a new AEWR methodology. A recent EPI post describes in detail how the new Trump AEWR will cut wage rates dramatically by using an inferior data set for agriculture and creating two artificial “skill levels,” which set H-2A wages at the 17th percentile of wages surveyed for farm occupations (skill level 1) and at the 50th percentile, which is the median of wages surveyed (skill level 2).

In the new AEWR, the Trump DOL also removes the previous H-2A program requirement that employers pay for 100% of housing costs for H-2A workers. In its stead, the new AEWR deducts a set amount out of every hour of an H-2A worker’s pay, to compensate the employer for H-2A housing costs. This shifts housing costs to H-2A workers who will have the added burden of paying for housing costs out of the already-low wages they earn. The housing deduction is subtracted from the AEWR—lowering a low wage even further—so low that in many states, the state minimum wage will be higher and become the de facto AEWR.

In total, DOL estimates that over $1.7 billion will be transferred from H-2A workers’ pockets back to farm employers under the new wage rule in 2026, amounting to $24 billion over the next 10 years as the program grows to over 500,000 jobs. EPI’s own estimates are that H-2A workers will see a wage cut of between $1.7 billion and $2.1 billion in 2026, depending on how state minimum wage laws are enforced. Reducing the AEWR for H-2A workers will also lower wages for U.S. farmworkers—one-third of whom are U.S.-born citizens, according to the latest DOL survey. A fall in the H-2A wage will increase demand for H-2A workers, since employers can save significantly on labor costs if they hire them. As a result, it will become relatively more expensive to hire non-H-2A U.S. farmworkers. Employers will therefore reduce demand for U.S. farmworkers, putting downward pressure on their wages, with U.S. farmworkers seeing wage reduction of $2.7 to $3.3 billion in annual pay.

This would represent a shocking upward redistribution of income away from some of the country’s most underpaid and essential workers for the food system.

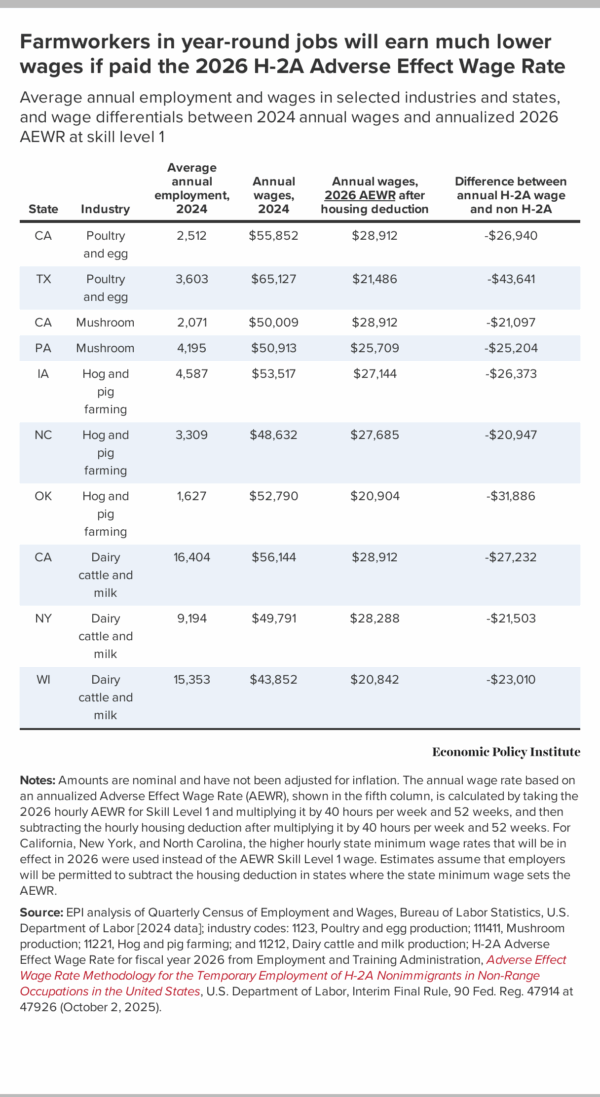

Under the new AEWR, H-2A farmworkers in year-round jobs would be paid tens of thousands of dollars less annually compared with what U.S. farmworkers earn now

The wage cuts from the AEWR described above currently apply only to H-2A farmworkers, who can only be employed in seasonal jobs. However, if the rider to make H-2A year-round goes into effect, farmworkers in year-round jobs will see the biggest pay cuts.

Table 2 lists a sample of some of the main year-round agricultural industries in major agricultural states, along with average annual employment, which together accounts for about 15% of the total year-round full-time equivalent jobs in agriculture. Table 2 shows how much farmworkers earned annually, on average in 2024 in those industries and states, and compares the annual earnings of farmworkers in 2024 with what H-2A workers would earn in 2026 if they had worked in the same jobs and had been paid the corresponding 2026 AEWR at skill level 1 for the entire year (40 hours per week for 52 weeks), minus the annualized amount that will be deducted from hourly wages for housing according to the 2026 AEWR.

The final column in Table 2 shows a few examples that illustrate the difference between what year-round U.S. farmworkers in the selected industries earned in 2024 and what H-2A workers at skill level 1 would earn if they were paid the annualized AEWR in 2026. Table 2 shows that the reduction in wages for H-2A farmworkers in year-round jobs could range from an annual pay cut of nearly $21,000 for farmworkers on hog and pig farms in North Carolina to a pay cut of almost $44,000 for farmworkers on poultry and egg farms in Texas.

Outcomes such as these—in which farmworkers paid the 2026 AEWR would earn tens of thousands of dollars less than what U.S. farmworkers earned in major year-round jobs in 2024—are egregious and in violation of the spirit and letter of the AEWR and the H-2A statute, but will be the norm and allowed if the year-round H-2A provision in the rider becomes law. This would hurt some of the most vulnerable and lowest-paid workers in the U.S. labor market and create an almost unstoppable incentive for employers to replace their current farmworkers who now fill year-round jobs with H-2A workers who can’t easily switch employers or effectively complain when their wages are stolen and when they’re forced to work in unsafe conditions.

Table 2

The year-round H-2A rider with the new AEWR rule could triple the current size of the H-2A program and cause wages to drop sharply for farmworkers

The year-round H-2A rider with the new AEWR rule could triple the current size of the H-2A program and cause wages to drop sharply for farmworkers

The ultimate result of the new H-2A wage rule combined with making the H-2A program year-round would be a likely tripling of the size of the H-2A program to about 900,000 workers, which includes the complete decimation of job quality for the 410,000 jobs in agriculture that can provide stable year-round employment and sometimes a living wage for U.S. farmworkers.

How would this occur? The Trump DOL’s new wage rule estimates that the lower pay for farmworkers it institutes will encourage farms to rapidly increase hiring through the H-2A program, estimating that 515,000 H-2A workers will be employed in 2034. If those low wages remain in effect and the year-round H-2A rider becomes law and is renewed yearly (as the H-2B riders have been every year), employers are likely to ramp up hiring for year-round jobs until nearly all are filled by H-2A workers who can be paid extremely low wages and, because of their precarious immigration status, have little bargaining power or the ability to complain in the face of employer lawbreaking.

For context, the 410,000 H-2A workers in year-round jobs plus the estimated 257,500 year-round equivalent jobs done by H-2A workers in seasonal jobs (i.e., 515,000 H-2A workers employed in 2034 for six months out of the year), would equal 667,500 full-time equivalent jobs in agriculture, or roughly 42% of all annual average employment in agriculture.

Instead of ballooning the H-2A program, policymakers should create a pathway to citizenship for farmworkers to ensure their rights on the job

Policymakers and the public must reject the harmful and unjustified proposals coming from Trump and Congress to pay less to farmworkers who already live on the margins of society, and to keep more of them indentured through the H-2A program. This rider is another example that reveals the truth about the Trump administration’s immigration agenda: They have no real interest in protecting jobs or pay for American or “native-born” workers, only in giving employers what they demand.

Using H-2A, a problematic temporary work visa program—in which workers are virtually indentured to their employers and that accounts for most of the wage and hour violations that take place on farms—to fill permanent, year-round jobs should give pause to all members of Congress. It makes no sense, unless the goal is to keep the workers employed in those jobs from having equal rights and fair pay. If migrant workers are filling true labor shortages in permanent, year-round jobs, then those workers should always get lawful permanent residence (i.e., green cards) that puts them on a path to citizenship.

If members of Congress want a reliable, healthy, and stable farm labor force that can continue to produce food domestically for Americans, they should pass legislation that legalizes undocumented farmworkers and reforms the H-2A program so that all migrant farmworkers have equal rights, fair wages, and a quick path to permanent residence and citizenship. That’s the only way to ensure that the workers who sustain the food supply chain will be treated with the dignity and respect they deserve and that honors their contributions to the U.S. economy.

The amounts have not been adjusted for inflation. The 2026 AEWR provides two “skill levels” for farmworkers—which are set at specific percentiles along the distribution of OEWS wages surveyed. Skill level 1 is the 17th percentile while skill level 2 is the median of wages surveyed, which is also the 50th percentile. For this calculation, I am only calculating the wage differentials for H-2A workers in year-round jobs who are classified by employers at skill level 1, which DOL estimates will account for 92% of all H-2A workers.

DOL’s new Adverse Effect Wage Rate will result in a pay cut for H-2A workers and U.S. workers that will line the pockets of employers by billions

DOL’s new Adverse Effect Wage Rate will result in a pay cut for H-2A workers and U.S. workers that will line the pockets of employers by billions

The year-round H-2A rider with the new AEWR rule could triple the current size of the H-2A program and cause wages to drop sharply for farmworkers

The year-round H-2A rider with the new AEWR rule could triple the current size of the H-2A program and cause wages to drop sharply for farmworkers

Once the official FSA data are released and hopefully return to a normal schedule, our

Once the official FSA data are released and hopefully return to a normal schedule, our

Recent comments